Java for Everything

June 1, 2014

I used to ask interviewees, “What’s your favorite programming language?” The answer was nearly always, “I just choose the right language for the job.” Duh. Does anyone ever deliberately pick the wrong language? This was clearly a way to avoid actually naming a language for fear of picking one I didn’t like.

If the interviewee gave an answer at all, it was, “I’m most familiar with language X,” which didn’t answer my question either.

At the time I would myself have replied something like, “I like Python best because it makes me happy to program in it, but I only use it in such-and-such a situation. The rest of the time I use XYZ…”

About a year ago, though, I started to form a strange idea: That Java is the right language for all jobs. (I pause here while you vomit in your mouth.) This rests on the argument that what you perceive to be true does not match reality, and that’s never a popular approach, but let me explain anyway.

Python really is my favorite language, and it truly makes me happy when I code in it. It pushes the happy spot in my head. It matches pseudo-code so well that it’s a genuine pleasure to work in it.

Years ago I read Bruce Eckel’s influential Strong Type vs. Strong Testing. In it he argued that static typing (what he calls strong typing) is one of the many facets of program correctness, and that if you’re going to check the other facets (such as the algorithm and the logic) with unit tests, then the types will also get checked, so you may as well go for dynamic typing and benefit from its advantages.

Bruce used Python to illustrate his code, and that clinched it: I decided that I would from then on write everything in Python. Unfortunately I was half-way through a large Java program at work, but my co-worker and I agreed that it should have been written in Python, and perhaps one day we’d get a good excuse to rewrite it all that way.

Several things changed my mind 180° in less than a year:

-

At one company I wrote a simulator that allowed me to run my Java services without a fully-functional site. In this simulator I ran scripts that tested various scenarios including failures. For these scripts I decided to use JavaScript, primarily because it’s included in Java 6 and secondarily because many people know it. I reasoned that a scripting language would allow us and Q/A to write tests easily. An intern, Justin Lebar, argued that we should simply use Java. The simulator is in Java, so why not write the scripts in it too? It’s sitting right there and we all know it. I went ahead with JavaScript, which forced me to write various code to bridge the two. It also meant that stack traces were much harder to read, since they didn’t point to the line in the script that was being executed. Q/A never wrote any tests. Overall we gained nothing from JavaScript and Justin had been right.

-

At the same company we stored our logs in JSON format (which is a great idea, by the way), and a co-worker wrote a Python program called

logcatto parse the logs and generate the standard columnar output, with many nice features and flag (including a binary search for timestamp). On OurGroceries, my personal project, we needed something similar and I suggested again to use Python. My partner Dan Collens suggested Java, since it’s right there and we know it and it’s fast. He wrote it and he was right: it’s blazing fast. I’ve since compared the Python logcat to a Java one and the latter is about ten times faster. Whatever time was saved by the developer when writing the Python code (if any) were lost many times over as dozens of users had to wait ten times longer each time they fished through the logs. -

And finally, I went to write a simple program that put up a web interface. I considered using Python, but this would have required me to figure out how to serve pages from its library. I had already done this in Java (with Jetty), so I could be up and running in Java in less time. I realized that as I accumulate knowledge about 3rd party Java libraries and grow my own utility library, it becomes increasingly expensive to use any other language. I have to figure those things out again and write them again, instead of copying and pasting the code from the previous project. Note that this doesn’t argue for Java, but it does argue for using a single language.

The big argument against Java is that it’s verbose. Perhaps, but so

what? I suppose the real argument is that it takes longer to write the code. I

doubt this is very much true after the first 10 minutes. Sure you have to

write public static void main, but how much time does that take? Sure you

have to write:

Map<String,User> userIdMap = new HashMap<String,User>();

instead of:

userIdMap = {}

but in the bigger scheme of things, is that so long? How many total minutes out of a day is that, two? And in Python the code more realistically looks like this anyway:

# Map from user ID to User object.

userIdMap = {}

(If it doesn’t, then you have bigger problems. Undocumented Python programs are horrendously difficult to maintain.) The problem is that programmers perceive mindless work as painful and time-consuming, but the reality is never so bad. Here’s a quote from a forum about language design:

It really sucks when you have to add type declarations for blindingly obvious things, e.g. Foo x = new Foo(). – @pazsxn

No, actually, typing Foo one extra time does not “really suck”. It’s three

letters. The burden is massively overstated because the work is mindless, but

it’s really pretty trivial. Programmers will cringe at writing some kind of

command dispatch list:

if command = "up":

up()

elif command = "status":

status()

elif command = "revert":

revert()

...

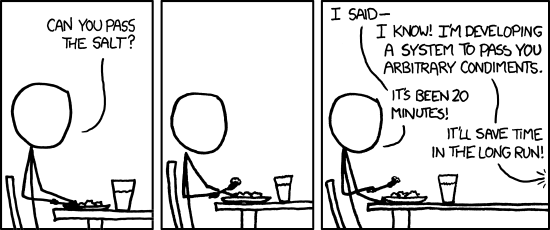

so they’ll go off and write some introspecting auto-dispatch cleverness, but

that takes longer to write and will surely confuse future readers who’ll wonder

how the heck revert() ever gets called. Yet the programmer will incorrectly

feel as though he saved himself time. This is the trap of the dynamic language.

It feels like you’re being more productive, but aside from the first 10 minutes

of a new program, you’re not. Just write the stupid dispatch manually and get

on with the real work.

(Aside: I’m on the wrong side of a different decision, the one to use vim for code editing. I feel very efficient when using vim, as code flies around the terminal, and I feel sluggish using Eclipse, and justify my choice with this efficiency argument. But surely all my gains are lost the first time I have to look up who calls a particular function, or when I have to look up the methods of an object manually. I recognize that I’m wrong on this one in the same way that dynamic language apologists are about their choice.)

So why are dynamic languages ever chosen? If you and I have a contest to write

a simple blogging system and you’re using (say) Python, you’ll have something

interesting in 30 minutes using pickling and whatnot, and it’ll take me two

days to build something with MySQL. Many language choices are based on trivial

contests like these. But after two weeks of development, when we both have to

add a feature, mine will take at most as long as yours, and I won’t be spending

any time figuring out how to get my system to handle so many users, or tracking

down why some obscure if clause breaks because you misspelled the name of a

function, or figuring out what the heck this request parameter contains.

The classic hacker disdain for “bondage and discipline languages” is short sighted; the needs of large, long-lived, multi-programmer projects are just different than the quick work you do for yourself. – Source

And you don’t think you’ll struggle with scalability sooner than I? Every year the NaNoWriMo website goes down on October 31st. It’s unresponsive for days. About 60,000 people hit it over a period of several hours, so maybe four requests per second. It’s written in PHP. The OurGroceries backend is written in Java. It handles (currently) about 50 complex requests per second and the CPU rarely goes above 1% for the Java process.

Twitter recently tripled their search speed by switching their search engine from Ruby to Java.

A year earlier, Joel Spolsky tweeted:

Digg: 200MM page views, 500 servers. Stack Overflow: 60MM page views, 5 servers. What am I missing?

— Joel Spolsky (@spolsky) October 13, 2010The reply from @GregB was:

> @spolsky: Digg: 200MM page views, 500 servers. Stack Overflow: 60MM page views, 5 servers. What am I missing? << That's the PHP factor

— Greg Brant (@GregB) October 13, 2010StackOverflow uses ASP.NET. So you can complain all day about public static

void main, but have fun setting up 500 servers. The downsides of dynamic

languages are real, expensive, and permanent.

And what about the unit testing argument? If you have to unit test your code anyway, what does static typing buy you? Well for one thing it buys you speed, and lots of it. But also writing and maintaining unit tests takes time. Most importantly, the kinds of bugs that people introduce most often aren’t the kind of bugs that unit tests catch. With few exceptions (such as parsers), unit tests are a waste of time. To quote a friend of mine, “They’re a tedious, error-prone way of trying to recapture the lost value of static type annotations, but in a bumbling way in a separate place from the code itself.”

So here’s my new approach: Do everything in Java. Don’t be tempted to write some quick hack in Python because:

-

You can’t copy and paste code from other projects in your primary programming language.

-

It may feel faster to develop, but that’s an illusion. The actual time saved is small, though admittedly annoying.

-

It’s one more language, platform, and set of libraries that I and my co-workers have to learn and master.

-

And here’s the important one: Chances are good that this quick hack will grow and become an important tool, and I won’t have the bandwidth to rewrite it, yet I’ll suffer the performance and maintenance penalty every time I use it.

I agree it’s fun to develop in Python. I love it. When I’m writing a Sudoku solver, I reach for Python. But it’s the wrong tool for anything larger, and it’s the wrong tool for code of any size written for pay, because you’re doing your employer a disservice.

I’m even taking this to an extreme and using Java for shell scripts. I’ve found that anything other than a simple wrapper shell script eventually grows to the point where I’m looking up the arcane syntax for removing some middle element from an array in bash. What a crappy language! Wrong tool for the job! Write it in Java to start with. If shelling out to run commands is clumsy, write a utility function to make it easy.

I’ve also written a java_launcher

shell script that allows me to write this at the top of Java programs:

#!/usr/bin/env java_launcher

# vim:ft=java

# lib:/home/lk/lib/teamten.jar

I can make the Java programs executable and drop the .java extension. The

script strips the header, compiles and caches the class file, and runs the

result with the specified jars. It provides one of the big advantages of

Python: the lack of build scripts for simple one-off programs.

This focus on a single language has had an interesting effect: It has encouraged me to improve my personal library of utility functions (teamten.jar above), since my efforts are no longer split across several languages. For example, I wrote a library that contains image processing routines. They’re both faster and higher quality than anything you can find in Java and Python. This took a while, but I know it’s worth it because I won’t find myself writing some Python script and wishing I could resize an image nicely. I can now confidently invest in Java as an important part of my professional and personal technical future.

There remains the question of why choosing Java specifically, out of the set of compiled statically-typed languages. The advantages of C and C++ (slight performance gains, embeddability, graphics libraries) don’t apply to my work. C# is nice but not cross-platform enough. Scala is too complex. And other languages like D and Go are too new to bet my work on.

When I tell people that I now write everything in Java, they look horrified. One friend had a visible look of disgust. But you know, Java’s a pretty nice language, and when my code compiles, which is often the first time, it’ll usually also run correctly. I don’t have that peace of mind with any other language. Java just works like a horse and is useful across a very broad range of applications.